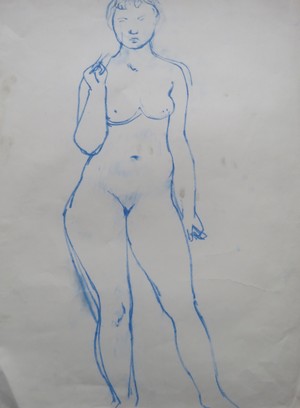

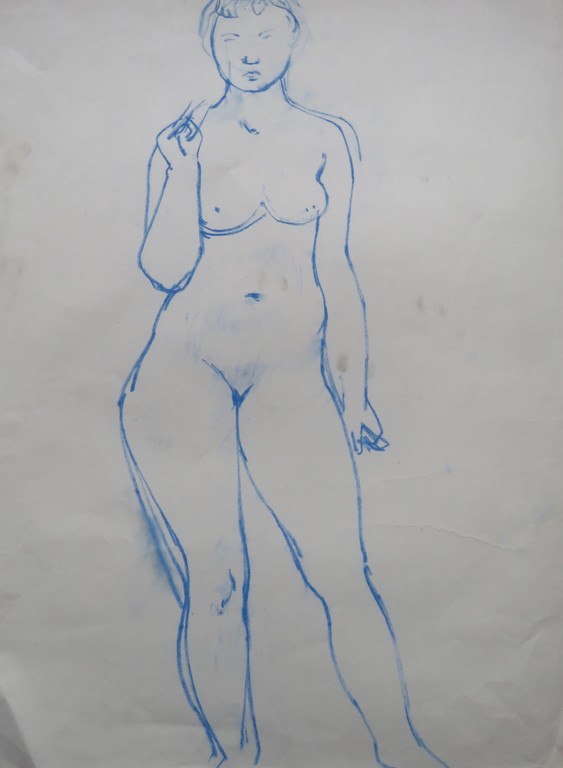

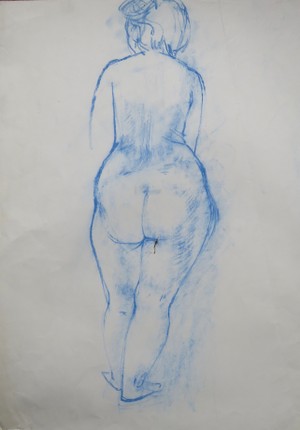

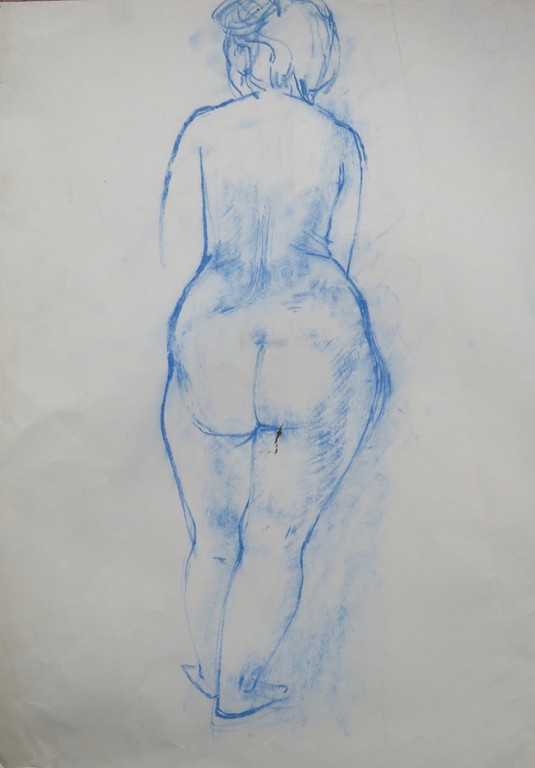

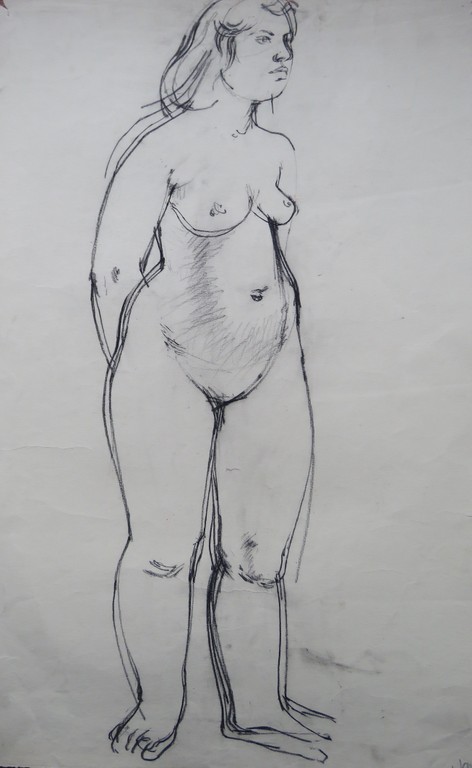

Life Drawing

Life Drawings by Janie Alston, 1952-57

Above are some of my Janie Alston life drawings from her time at Glasgow School of Art during the 1950s. They show the influence of the teaching at GSA. William Drummond Bone’s principles; encouragement of using materials like charcoal, red conte, ink to free; space filling; finding the form (before details); looking at the tension in the form, the taut line and the slack line…

Janie remembers some of the characters amongst the models. One girl, Natalina Tedesca, whose father did not know that she was posing in the nude, was always looking for portraits of herself clothed.

Natalina once bought a portrait bust of herself to show her dad. She told Janie that she had put some lipstick on the sculpture and dressed it with a hat, putting it in her window. Sometimes Natalina would wear boots as she was posing because she felt the cold.

The picture of the Sculpture studio at GSA shows the model, ‘Big Jimmy’, posing for the students. According to Janie, he would only do a few set poses. Normally he posed with his hand behind his back, because he had a few fingers missing.

A current exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art, entitled ‘From Life’, is showing work that relates to the history of life drawing in the art school system. Disappointingly it did not show many actual drawings from the 250 years of the RA, which would, I feel, have been revealing about the evolution, or changing trends, or the impact of various tutors, in life drawing through the centuries.

In most art schools across the country, up until the late twentieth century, life drawing was core to any young artist’s education. I believe life drawing continues to be of utmost importance to young students today. The act of observing and drawing from life is crucial, in gaining understanding not just of the human form, but of actually questioning what we see. Looking and trying to record, with honesty, what is in front of the eye, requires concentration, openness, an ability to select marks appropriate to conveying the image, and stamina (there will be lots of mistakes along the way). It is akin to practicing scales and arpeggios, allowing time to perfect technical ability. But, in drawing the human figure, it also allows us to understand ourselves better, our form, our proportions, our physiological qualities.

Document Actions